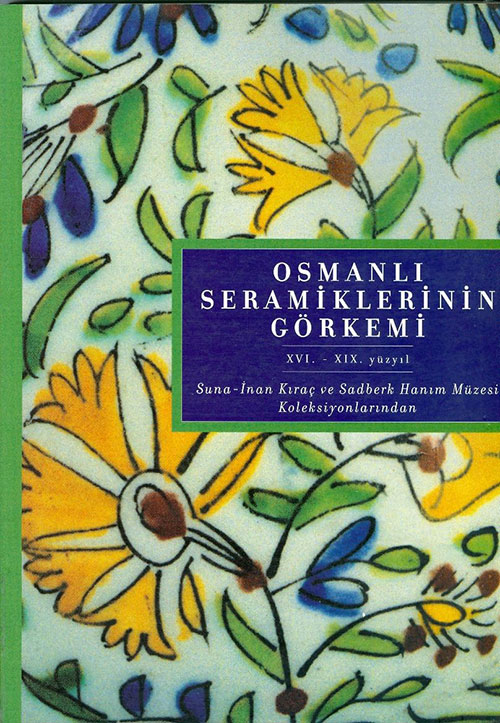

| Author | Laure Soustiel – Nicolas Sainte Fare Garnot (kürator) |

| Material Type | Book |

| Year | 2000, İstanbul |

| ISBN No | 9757078077 |

| Dimensions | 300×210 mm |

| Page | 222 pp, paperback |

| Figure | 178 ill. |

| Language | in Turkish and French |

| Series | Suna and İnan Kıraç Research Institute on Mediterranean Civilizations Institute Publications 6 |

Summary

Catalogue of the exhibition held at Musée Jacquemart – André in Paris from 1st April to 2nd July 2000, 222 pp, col. ill., in French.

When the Turks conquered Anatolia in the late 11th century, they brought with them many ceramic techniques peculiar to the Seljuks from Iran and took over the local Byzantine traditions. In order to reinforce their rules, the Seljuk sultans undertook the construction important projects which were embellished with tiles. One of the most outstanding examples of Seljuk art, these tiles decorated the mosques, madrasas, tombs and palaces. The most important tile production centre of the time was at the capital Konya.

The Byzantine pottery traditions existing in Anatolia, Cyprus and Syria continued their existence during the Anatolian Seljuk period as well.

New tile workshops were opened in Bursa and Iznik in the Emirates Period, i.e. 14th – 16th centuries. A new decorative technique imported from Iran, not known in Anatolia until then, came into use in the beginning of the 15th century and stayed so until mid-16th century. These tiles are known as cuerda seca, literally “dry cord”, or coloured glaze technique which was applied on paste with silica. Coloured glazes spread on various motifs side by side were separated from each other by a cord or a manganese mixture which turned black during firing. The very textile-like designs comprising flowers, plants, arabesques and geometric motifs were coloured with cobalt blue, turquoise, white, pistachio green, purple, yellow and black.

The political achievements of the Empire were accompanied with important artistic processes. The artistic tradition was under the protection of the sultans who not only thought of expanding their territories but also of developing art and architecture. The Ottoman sultans collected the enchanting Chinese porcelains with passion. Mehmed II usually ate from a Chinese porcelain plate. These Chinese porcelains first came as booty from battles; then they were imported by merchants specially for the sultans as of the 16th century; and then during the 17th and 18th centuries they were usually presented as gifts to the sultans, thus creating a world-famous collection. These porcelains always inspired the Ottoman artists, who started with imitating them.

A tile workshop was established near the palace in order to supply only the needs of the palace and especially the buildings built in the palace between 1510 and 1550 were decorated with them. The tile workshop of the palace rivalled those at Iznik in the first half of the 16th century.

About 1470-80 a new technique was developed from paste with silica at Iznik solely for the purpose of imitating the blue-white Chinese porcelain; they attained an unparalleled and undisputable level of authenticity about the mid-16th century. New colours were invented: turquoise blue toward 1525, olive green and light purple about 1540-45; thus, the new ceramics were enriched with naturalist floral compositions. Finally the world-famous “Iznik red” applied under the glaze was invented about 1555-57. Numerous plates, beakers, candlesticks, pitchers and mugs marked the peak of the production.

As of the end of the 15th century, Kütahya also started to produce ceramics with silica and bearing the same type of decoration in parallel to Iznik. In the early 17th century the Iznik fell short of supplying the demand, thus Kütahya workshops started to take over some of the work load.

In Kütahya, very fine ceramics were produced from paste with silica characterised with a very bright lemon yellow in the early 18th century. As of the second half of the 18th century both the technical and aesthetical aspects deteriorated. In addition to floral compositions, human and animal figures also started to appear.

The economic and political decline of the Ottomans Empire fell into about the late 17th century was also reflected in the decline of the state workshops. The palace was more interested in the European porcelains specially produced for the “East”, thus the workshops at Iznik did not run any more. Therefore, provincial workshops emerged to supply the needs of the domestic demand. Such local workshops produced “popular” or “folkloric” ceramics, very plain in look and considered traditional.

One such site with local production was at Çanakkale located on the Asian bank of the Hellespont (Dardanelles); and Çanakkale ceramics display an incredible variety in form and decoration.

The present exhibition catalogue contains not only introductory texts about these sites and Ottoman ceramic art but also inventorial information on 177 items from the Suna and İnan Kıraç collection and Sadberk Hanım Museum collection.